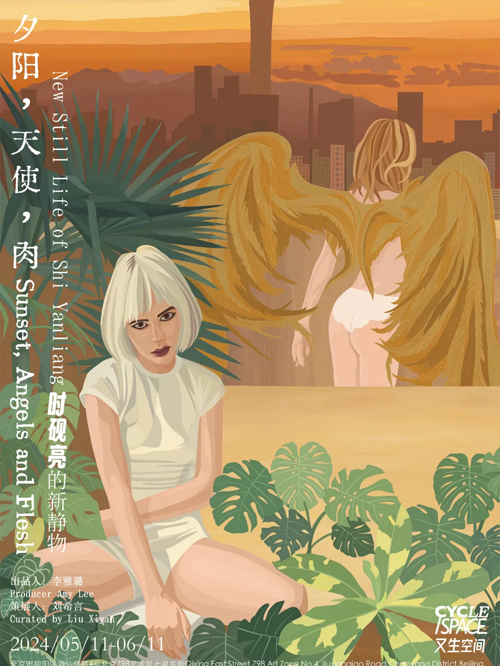

今年开春时候,时砚亮在一个傍晚打开窗户,夕阳的余晖勾勒出窗外楼宇的剪影,借由云霞与这个城市中许多虚虚实实的符号连接在一起。同时,玻璃上折射出的光线又在某个角度让他目眩,甚至能够在强光的细尘中微妙地捕捉到一些天使来过的痕迹。这扇窗户在时砚亮眼前成了一个取景框,远处的景物、窗前的植物与想象中的人物,在此刻静止。时砚亮当时记录下了这个场景《夕阳天使》,他仿佛捕捉到了一些通过“物”来理解自我和时代的信号,那种既世俗又神圣、既充满希望又似有警示的信号,但他还没有想好应该怎样描述它们。

这些信号其实是艺术家观察世界的方式,兼具宏观的时代背景和细微的具体物象,让人不禁联想到望远镜和显微镜同时出现的17世纪,光学带来的更大和更小的视角,改变了艺术创作的题材、手段和意涵。虽然此时的数字具身替代了彼时的自然主义作为催化剂,但后者导向的艺术趋势却一定程度上可以作为理解当下艺术风格以及时砚亮的一把钥匙,也就是现在看来很寻常的题材“静物”。

较晚成科的静物画,从来不是简单地对具体的“物”进行描绘,即便17世纪的静物画家怀揣着去叙事、去神性的创作初衷,但这一初衷的存在本身,就赋予了静物画抗争和反思的属性,而画面主体的日常性又在不断消解着前者。这既解释了当时静物画时而丰饶时而虚无的两面倾向,也赋予了静物画作为缓解时代焦虑或者是弥合时代缝隙的可能性。换句话说,当一个个体,或是一个群体,处于两种情感的交弥、两种媒介的交错时,静物,可以作为他们再认识世界的一个渠道。物的细微处是好奇和趣味,静止的空间大环境是对现实此刻的一种掌控,当然还有人物和人物活动的痕迹在这个场景中,他们是物的创造者和使用者,也是被物化的对象,他们不是某个具体的人,而是一些更丰富意蕴的载体。

近两年,时砚亮创作了一批与物相关的作品,它们有的以城市华光作为背景,辅以他对时代迷局的忧思;有的对房间一角细致打磨,展示他在审美趣味上的实验;有的是一些视觉符号的重组,描述他对意义的困惑。画中的主角有时是人物、有时是动物、有时是食物,但对时砚亮来说,它们统一是“静止在此刻的物”。此刻,是一个他处于由个人成长向家庭责任过渡的阶段、是一个传播媒介快速更新的新时代,是一个意义不断被新意义覆盖的时刻。而物,是所有被牵引至其中的对象,窗边迎着暮霭的白鹅、衔于少女唇边的花瓣、掩在叶脉下的兔子、遗落在桌椅上的布偶、重复的壁纸图案,和一块仿佛来自布克莱尔(Joachim Beuckelaer,16世纪晚期的尼德兰风俗画家、静物画家)画中的半扇肉排。它们或许都曾经来自某个故事,未来还将被赋予其他含义。然而,通过在此刻的观察、想象和排演,它们成为了时砚亮笔下的“静物”元素。从某种程度来看,并不是时砚亮有意以静物为题材去创作,而是创作初衷和画面关照上的矛盾性,让静物画成为了一个解释时砚亮的渠道。

静物画的元素在时砚亮的早期作品中就有端倪,“西瓜山”系列中不仅有常规意义上的静物——西瓜、苹果、橘子、兔子、石膏像等,画面的布局和气氛还让人联想到一些具有象征意涵的静物画,比如《榅桲、卷心菜、西瓜和黄瓜》(Quince, Cabbage, Melon, and Cucumber,Juan Sánchez Cotán,1602),或者《生命万岁》(Viva la Vida,Frida Kahlo,1954)。时砚亮以儿时的西瓜山记忆和实则象征血液与肉身的西瓜,隐喻了少年到青年、求学到入世的人生阶段,画中有鲜红旺盛的生命力,也有隐在不可知中的少年的自己。此类具有象征的静物元素在他几个阶段的作品系列中都有出现,比较常见的有鹅、肉、盆花和龟背竹、动画形象、地毯和壁纸、夕阳和窗户等,这些元素的反复恰好反映出他身上的矛盾性,既向往爱与欲,又保持一些天真与克制。对于呈现这些静物的环境,时砚亮营造出两种不同的气氛,由黑色背景布置的舞台桌面和开敞明亮的超现实空间,这是他不同时期的心境所致,也是对程式化自我的反抗。如同早期静物画的寓意,不仅是自然的镜子,也是生活的侧面;不仅要表现美好的现实,也要认识到这种美好只是暂时的;不仅要有道德美德方面的劝诫,也要以新的画面内容和表现形式去抗争旧有的规训方式。

值得一提的是,时砚亮画中的人物,甚至是一些被单独拎出来的人物,除了包含对消费时代将人物化的反思,还可以作为思考造物者的一条线索。静物的创造者并不是一直都是人,在过去,静物曾被认为是死物或者是神造物,随着机械论和人文主义对物与人的关系的讨论,物开始作为世界的组成部分,人成为了物的创造者,这才促成了静物画作为一个象征性画种的可能性。对时砚亮来说,人与物都是这个“静止在时刻的物”的组成部分,他既记录那些完整的场面,也记录一些局部。这还可以进一步解释时砚亮的画面技法,他始终追求一种光滑的物的边缘,放弃色块和笔触的过渡,甚至在新作中用了一些特殊的手法来强化硬边效果。这一如同切割的效果实则加重了作品的局部感,暗示了这些作品仿佛是从一件更完整的作品上切下来的,也寄托着时砚亮对形式语言重组的一种愿望。

至此,如果我们将整个展览想象成一张更大的静物画,分散的局部作为“物”组成了时砚亮的一次表达:一场现代都市的《盛宴》,一阵稍纵即逝的霞光,一些作为旁观者的物,在不同角度观察着和想象着它的造物者。为此,展览在入口墙面设置了几个窗口,借由观看者不同角度的视线,使这张静物画在现场完成。它一定是既轻松的又仿佛意有所指的,一定是既现实的又超现实的;同时,它一定不是一组连续性的故事情节,一定不是某个经典的静物题材。让我们回到展览的题目,它或许应该是一张新静物,一张包容矛盾和认识世界的新静物画。

As spring unfolded this year, Shi Yanliang opened his window one evening to find the setting sun's golden rays tracing the silhouette of buildings beyond. Linked by rosy clouds, these structures seemed to connect with the city's many real and imagined symbols. Meanwhile, light refracting through the glass dazzled his eyes, revealing subtle traces of angels in the dust motes dancing in the bright beams. The window became a viewfinder for Shi Yanliang, framing the distant scenery, the plants by the window, and imagined figures in a moment of stillness. He captured this scene in his artwork "Angel of The Setting Sun", as if he had grasped signals that revealed his understanding of self and era through "objects" — signals that were both mundane and sacred, hopeful yet cautionary. However, he was still pondering how to articulate them.

These signals reflect the artist's way of observing the world, encompassing both the vast historical backdrop and intricate details, reminiscent of the 17th century when telescopes and microscopes emerged, offering new perspectives that transformed artistic themes, techniques, and meanings. Although digital embodiment has replaced naturalism as a catalyst, the artistic trends influenced by the latter still hold the key to understanding contemporary artistic styles and Shi Yanliang's works. One such seemingly ordinary subject is "still life.”

The genre of still life painting, which developed later, has never been a mere depiction of specific "objects." Even in the 17th century, when still life painters aimed to narrate and deify their creations, this intention itself endowed the genre with attributes of resistance and reflection. The everyday nature of the subjects constantly dissipated these deeper meanings. This explains the dual tendency of still life paintings— sometimes abundant, sometimes ethereal — and grants still life the potential to alleviate the anxieties of the times or bridge the gaps between epochs. In essence, when an individual or a group finds themselves at the intersection of emotions and mediums, still life serves as a gateway to re-recognizing the world. The intricacies of objects pique curiosity and delight, while the static spatial environment offers a sense of control over the present reality. Of course, traces of people and their activities are also present in this scene. They are creators and users of objects, as well as objects of materialization. They are not mere individuals but carriers of deeper meanings.

In recent years, Shi Yanliang has created a series of works centered around objects. Some feature the urban splendor as a backdrop, interspersed with his contemplations on the enigmas of the era. Others delicately capture corners of rooms, showcasing his aesthetic experiments. Still, others are reconstructions of visual symbols, expressing his confusion about meaning. The protagonists in these paintings are sometimes people, sometimes animals, sometimes food, but for Shi Yanliang, they are unified as "objects frozen in time." This moment represents a transitional phase in his life, from personal growth to assuming familial responsibilities, and it coincides with a new era of rapidly evolving media and constantly shifting meanings. Objects are all the entities drawn into this flux— a white goose greeting the twilight by the window, a petal on a young girl's lips, a rabbit hidden beneath a leaf, a doll left on a chair, repeating wallpaper patterns, and a half-cut steak seemingly plucked from one of Joachim Beuckelaer's 16th-century paintings. These objects may have originated from stories and will undoubtedly acquire new meanings in the future. However, through observation, imagination, and rehearsal in the present moment, they become elements of "still life" in Shi Yanliang's artistic vision. To some extent, it's not that Shi Yanliang intentionally chooses still life as a subject; rather, the contradictions inherent in his creative intentions and visual representations make still life a channel for interpreting his art.

The elements of still life paintings were already evident in Shi Yanliang's early works. In his "WatermelonMountain" series, not only are there conventional still life objects like watermelons, apples, oranges, rabbits, plaster casts, but the layout and atmosphere of the paintings also evoke memories of symbolic still life paintings, such as "Quince, Cabbage, Melon, and Cucumber" by Juan Sánchez Cotán (1602), or "Viva la Vida" by Frida Kahlo (1954). Shi Yanliang metaphorically depicts the life stages from youth to adulthood, from study to worldly involvement, with the memory of his childhood, watermelons symbolizing blood and flesh. The paintings exude a vibrant, flourishing vitality, yet also hide the ineffable self of the youth. Such symbolic still life elements recur in his works across several series, including common motifs like geese, meat, potted flowers, rhizomatous monsteras, cartoon characters, carpets and wallpapers, sunsets, and windows. The repetition of these elements aptly reflects the contradiction within him, aspiring for love and desire yet maintaining innocence and restraint.

Notably, the figures in Shi Yanliang's paintings, even those depicted individually, serve not only as a reflection on the commodification of humans in the consumer era but also as a clue to ponder the creator. Still life creators were not always human. In the past, still life objects were considered inanimate or creations of the gods. With the discussion of the relationship between objects and humans by mechanism and humanism, objects began to be seen as part of the world, and humans became the creators of objects, paving the way for still life painting as a symbolic genre. For Shi Yanliang, both humans and objects are components of this "still object in a moment." He records both complete scenes and partials. This further explains his painting techniques, which consistently pursue a smooth edge for objects, abandoning transitions between color blocks and brushstrokes. Even in his new works, he employs special techniques to enhance the hard-edged effect. This cutting-like effect actually enhances the sense of locality in the works, suggesting that they seem to be excised from a more complete work, embodying Shi Yanliang's aspiration for the recombination of formal languages.

If we envision the entire exhibition as a larger still life painting, the scattered partials serve as "objects" that constitute Shi Yanliang's expression: a modern urban "feast," a fleeting ray of sunset, objects as observers observing and imagining their creator from different angles. To this end, the exhibition features several windows on the entrance wall, allowing the still life painting to be completed in situ through the varied perspectives of the viewers. It must be both relaxed and seemingly meaningful, both realistic and surreal. Simultaneously, it must not be a continuous narrative or a classic still life subject. Returning to the title of the exhibition, it perhaps should be a new still life, a new still life painting that embraces contradictions and comprehends the world.

时砚亮,1981年生于山东省,2004年至2008年就读中央美术学院,他的个展与部分群展包括:ArtPro藏家推荐展 - 时砚亮个展,ArtPro Space,北京,2023;日常的隐喻 - 时砚亮个展,hiart space,北京,2022;卡通的泡沫 - 时砚亮个展,PENGS SPACE,深圳,2021;晚霭 - 时砚亮个展,hi 艺术中心,深圳,2020;西瓜山 - 时砚亮个展,世纪翰墨画廊,北京,2010;穿越兔子洞——中国新绘画案例研究(三),又生空间,北京,2024;招牌动作,一条艺术空间,上海,2023;时间之锥,HANMO艺术中心,北京,2023;新绘画的崛起 - 一份80后艺术家的名单,玉兰堂,北京,2022;艺术凤凰2021 - 青年艺术100邀请展,凤凰艺都美术馆,无锡,2021;2021青年艺术100年度展,嘉德艺术中心,北京,2021;敬请赐福,山海美术馆,北京,2019;青衿计划,正观美术馆,北京,2018;思想的形状及其纬度展,世纪翰墨画廊,北京,2011等。

刘希言,博士,副研究员,中央美术学院美术馆策划研究部主任。曾任中央美术学院美术馆“CAFAM双年展”“CAFAM未来展”“北京国际摄影双年展”办公室成员。入选文旅部青年策展人扶持计划,策划展览获得文旅部馆藏精品展出季优秀展览项目。著有《建构与思辨:艺术博物馆陈列方法论研究》一书。学术论文散见《美术》《美术研究》《艺术设计研究》《艺术博物馆》《美术馆》等。